Gordon Monson: When the LDS Church alters classic art in the name of modesty, it does more harm than good

Such moves are an affront to women and make the church look not just prudish but also extreme.

To those making accusations that proper research wasn't done for a column about the LDS Church's altering a painting for modesty, I can assure you, it was done. The church confirmed to The Tribune that it had edited the depiction, and then had no comment. Thanks for reading.

Latter-day Saints alter a Nativity painting to make Mary more modest

New version removes cleavage in Carlo Maratta’s 17th-century artwork.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The Virgin laying the sleeping Christ on Straw

Ca. 1656. Oil on panel.On display elsewhere

This painting listed in the inventory of Queen Elizabeth of Farnesio offers a slightly varied reproduction of the central motive of the fresco of the Adoration of the Shepherds that decorates the Alaleone Chapel at the church of Sant’Isidoro Agricola in Rome. An early work, it was Maratti’s most important commission from the mid 1650s. This was the moment when he began to free himself from the influences of Raphael, Carracci, Reni and Correggio, opting for greater compositional freedom and movement favored by contrasting light and shadows. This is visible in the present small and very beautiful panel. Nonetheless, he never abandoned the measured and delicate gestures that mark his characteristically harmonious classicism and made him the most appreciated and influential Roman artist of the late 17th century (Text from La Belleza Cautiva. Pequeños tesoros del Museo del Prado, Museo Nacional del Prado, Obra Social la Caixa, 2014, p. 99).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints encouraged members to download a painting of Mary and the baby Jesus for Christmas, but it was an edited version — altered to remove a hint of Mary’s cleavage.

On its website, the church shared 18 Nativity images for members to retrieve and share or maybe use as a screen saver on their laptops, tablets or phones. One of those pictures is a painting by Italian artist Carlo Maratta from the 1650s of the Virgin Mary and the Christ child — except that someone modified the painting before sharing it on the website.

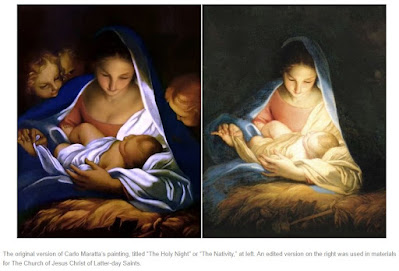

In the original Maratta painting, titled “The Holy Night” or “The Nativity,” small angels peek past Mary to gaze at the baby. In the church’s version, the angels have been removed.

(As of Wednesday, after an inquiry from The Salt Lake Tribune, the Maratta image had been removed from the website.)

In Maratta’s original, Mary shows a hint of cleavage as she gazes adoringly at her newborn. In the Latter-day Saint version, someone has not only given Mary a higher neckline but also moved a shawl a bit higher on her left shoulder, giving her added modesty after more than 3½ centuries.

The church declined to comment on the altered artwork.

The edited version of Maratta’s painting was created for the 2016 Light the World initiative, which is intended to encourage acts of Yuletide service. The original painting hangs in the San Giuseppe dei Falegnami church, next to the Forum in Rome.

When does a church’s effort to champion female modesty have a corrosive effect on the way women view and feel about their own bodies?

Too often.

There’s no shame in the natural female form. It’s a good guess that even God would agree with that, since if you believe in him, you figure he was the author of it. But you wouldn’t know that by the way The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — a faith, by the way, that preaches of a Heavenly Mother — attempts to keep it under wraps.

By now, you may have read in The Salt Lake Tribune about the Utah-based faith modifying classic works of art, including eliminating any hint of the Virgin Mary’s cleavage in Carlo Maratta’s 17th-century painting of the Nativity. In the church’s version, which had been made available on its website, Mary’s neckline is raised and a shawl covering her shoulder is a bit higher.

Not only are the alterations an affront to classic art — the church’s image also edited out surrounding angels depicted in the original — but they also either unwittingly or wittingly send the aforementioned message to women that there’s something shameful about their bodies. In other works, the church has previously covered the shoulders of female angels.

We get it. The church is all-in on modesty. But the attendant shame put upon women coming alongside that overemphasis on keeping themselves covered backfires on the church, not just in the harm it creates among women and women’s self-esteem, but also in sexualizing them as objects or, even worse, possessions.

Not good, brethren.

Ironically, news of this doctored photo emerges at a time when members are praising the church’s new principle-based “For the Strength of Youth” guidelines for backing away from proscriptive instructions on modesty.

Nothing wrong with respecting women; nothing wrong with modesty, but when the church drapes a shirt over the Virgin Mary in classic art, eliminating the slightest bit of cleavage, what exactly does that do? It draws more attention to that form, sexualizes it, even in a rendering that depicts the mother of the Lord in complete innocence, adoring her newborn.

It makes the church look not just prudish but also extreme.

Some experts believe such a heavy-handed approach to modesty becomes a controlling mechanism, a tool to suppress female expression and to — wrongly — make women feel as if they are responsible for men’s sexual thoughts.

For women, that modesty mechanism can cause fear and anxiety, they say, particularly when the boundaries for compliance are spelled out primarily by male church leaders.

If the church makes a big deal out of the hint of a woman’s cleavage then it becomes … a big deal. What it should be is … natural and normal, which is to say, it should be normalized.

Nobody’s saying here to be disrespectful, especially when it comes to such a revered character as Mary. The encouragement and point isn’t, from the church’s perspective, for it to encourage the flaunting of a woman’s body to the edge of abject immodesty, wherever that neckline or hemline is to be drawn.

And those lines should be drawn by each woman for herself.

It’s the overwrought and overbearing messages, the extremes, that do more harm than good, the insistence that women cloak themselves because doing otherwise, even to the point of showing a little shoulder or midriff or whatever, in real modern life or in a centuries-old painting, is disfavored on the one end or deplorable on the other.

Society has already done a negative number on the way too many women view their bodies. When faith leaders add to that number, women of all kinds, particularly females of faith, too often are made to look at themselves and feel what they should not feel — chagrin, dishonor, shame and disgrace.